Welcome to this second part in a series of articles about multithreading with C++11. In the previous part, I briefly explained what a thread is and how to create one with the new C++ thread library. This time, we will be writing a lot more code, so open up your favourite IDE if you want to try the examples while you’re reading.

In the previous article, we also saw that sometimes the output wasn’t completely right when running multiple threads simultaneously. Today, we’ll see some other problems with sharing a resource between threads and, of course, provide some solutions to these problems.

This is an article part of a series about multithreading with C++11, the other parts are listed below:

- Part 1: Introduction to threads with C++11

- Part 2: Protecting your data with multiple threads

Lost data

Let’s start with a simple example. Consider the following program:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <thread>

#include <vector>

using std::thread;

using std::vector;

using std::cout;

using std::endl;

class Incrementer

{

private:

int counter;

public:

Incrementer() : counter{0} { };

void operator()()

{

for(int i = 0; i < 100000; i++)

{

this->counter++;

}

}

int getCounter() const

{

return this->counter;

}

};

int main()

{

// Create the threads which will each do some counting

vector<thread> threads;

Incrementer counter;

threads.push_back(thread(std::ref(counter)));

threads.push_back(thread(std::ref(counter)));

threads.push_back(thread(std::ref(counter)));

for(auto &t : threads)

{

t.join();

}

cout << counter.getCounter() << endl;

return 0;

}

The purpose of this program is to count to 300000. Some smartass programmer wanted to optimize the counting and created three threads, each adding 100000 times one to a shared variable counter.

Let’s walk a bit through the code. We create a new class called Incrementer which holds a private variable counter. The constructor is straightforward, simply initializing counter by setting it to zero.

What follows is an operator overloading function, and in this case operator(). This means that each object of this class can be called as a simple function. Usually, you would call a method on an object like this: object.fooMethod(), but now, you can actually call the object, like this: object(). This is convenient because now we can pass the whole object to the thread class and, within the operator overloading function, use all the advantages of a class. The last method of the class is getCounter: a simple getter for the counter variable.

Then, we have the main() function; here, we similarly create threads as described in the previous article. A few differences, though: we now create an object of the class Incrementer, and we pass it to the threads. Note that we use std::ref here, to pass a reference of the object, instead of passing a copy to the thread.

So, let’s see what this program produces and if this smartass programmer is brilliant or stupid. Compile the program using GCC 4.7 or higher, or Clang 3.1 or higher. In the case of GCC, use the following command:

g++ -std=c++11 -lpthread -o threading_example main.cpp

And voilà, the output:

[lucas@lucas-desktop src]$ ./threading_example

218141

[lucas@lucas-desktop src]$ ./threading_example

208079

[lucas@lucas-desktop src]$ ./threading_example

100000

[lucas@lucas-desktop src]$ ./threading_example

202426

[lucas@lucas-desktop src]$ ./threading_example

172209

But wait a second! That smartass programmer wasn’t so smart after all! The program doesn’t count to 300,000; one run only reached 100,000! Why is this happening? Well, as simple as ‘increment by one’ sounds, it requires multiple instructions for the processor to increment a variable:

movl counter(%rip), %eax

addl $1, %eax

movl %eax, counter(%rip)

What happens is this:

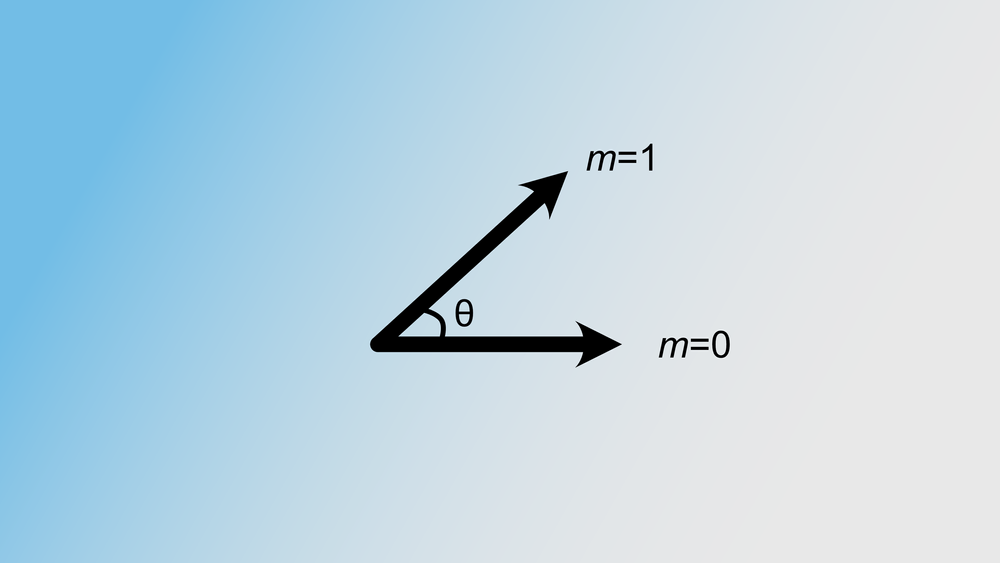

- We have the current counter value stored in memory, and we load that value into the EAX register

- We add one to the value in the EAX register

- We store the value in EAX back in the original memory location

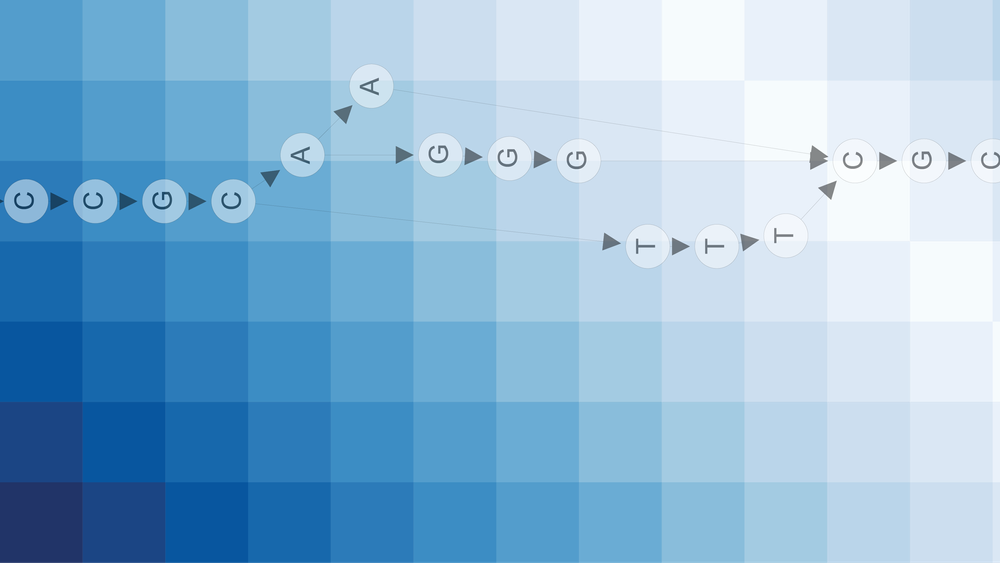

I hear you think, “Ok, nice information, but how does this solve my counting problem, smartass?” Remember from the previous article that threads shared the processor if there’s only one core. So at some point, one thread is happy because its instructions are executed for a while, but then the big boss operating system says, “Ok, time’s up, back in the line!” Then, another thread will be executed for a while. And when it’s the turn of the original thread again, he starts executing where he was left. So, can you guess what happens when the operating system decides to switch to another thread while the original thread is in the middle of incrementing a variable's value by one? Well, for example, this:

| Thread 1 | Thread 2 | Counter | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| %eax <- counter | nothing | 1 | The current value of the counter is now stored in EAX |

| %eax + 1 | nothing | 1 | The value in EAX is now 2, but the counter hasn't been updated yet |

| nothing | %eax <- counter | 1 | Hey, a switch to the other thread, and because the counter hasn't been updated, it loads the old value |

| %eax -> counter | nothing | 2 | And we're back at thread 1. When a thread switches, the state of the registers (for example EAX), are saved, and when we switch back, they're restored in their original state. Because EAX was two the last time thread one got interrupted, that value will be written in the counter variable. |

| nothing | %eax + 1 | 2 | And we're back at thread 2. The last time thread got interrupted, EAX had the value 1. |

| nothing | %eax -> counter | 2 | And because EAX was one (and is now two because of the previous instruction), the counter remains 2. |

Hey, it’s occupied!

The solution is to make sure only one thread can access the shared variable at the same time. This can be done using the std::mutex class. Visualize it as a sort of toilet: when you go inside, you lock it, do your stuff, and then you unlock it. Anyone who wants to use the bathroom has to wait before you’re ready.

A convenient feature of a mutex is that the operating system makes sure the locking and unlocking operations are indivisible. This means that the thread will not be interrupted when it’s trying to lock or unlock a mutex. When a thread locks or unlocks a mutex, this operation will be finished before the operating system switches threads.

And the best thing is, when you try to lock a mutex, but some other thread has already locked it, you’ll have to wait. But the operating system keeps track of which threads wait on which mutex. The blocked thread will go into a “blocked on m” state, meaning the operating system won’t give that thread any processor time until the mutex becomes unlocked. This means no wasted CPU cycles. If multiple threads are waiting, it depends on the operating system which thread will be the ‘winner.’ General purpose operating systems like Linux and Windows use a First In First Out system; on realtime operating systems, it’s priority-based.

Let’s modify the above code to make sure counting works as expected.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <thread>

#include <vector>

#include <mutex>

using std::thread;

using std::vector;

using std::cout;

using std::endl;

using std::mutex;

class Incrementer

{

private:

int counter;

mutex m;

public:

Incrementer() : counter{0} { };

void operator()()

{

for(int i = 0; i < 100000; i++)

{

this->m.lock();

this->counter++;

this->m.unlock();

}

}

int getCounter() const

{

return this->counter;

}

};

int main()

{

// Create the threads which will each do some counting

vector<thread> threads;

Incrementer counter;

threads.push_back(thread(std::ref(counter)));

threads.push_back(thread(std::ref(counter)));

threads.push_back(thread(std::ref(counter)));

for(auto &t : threads)

{

t.join();

}

cout << counter.getCounter() << endl;

return 0;

}

Note the changes: we included the mutex header file and added a member m to our class, with type mutex, the standard mutex class in C++11. In the method operator()(), we lock the mutex just before incrementing the counter, and afterwards, we unlock it again.

When we run the program, the output is correct:

[lucas@lucas-desktop src]$ ./threading_example

300000

[lucas@lucas-desktop src]$ ./threading_example

300000

And as always in computer science, there’s no free lunch. Using mutexes will considerably slow down your program, but that’s better than an incorrect program.

Heimdall, guard us against exceptions

When incrementing a variable by one, the chance of an exception being raised is not particularly high, but with more complex code, it’s definitely possible. The above code is not really exception-safe. When an exception occurs, the mutex will still be locked while the function is already finished.

To make sure the mutex is unlocked when an exception is thrown, we could use the following code:

for(int i = 0; i < 100000; i++)

{

this->m.lock();

try

{

this->counter++;

this->m.unlock();

}

catch(...)

{

this->m.unlock();

throw;

}

}

But that’s an awful lot of code for just locking and unlocking a mutex. Luckily, there’s a nice, simple solution for that: the std::lock_guard class. The lock_guard class is really simple: it locks the given mutex on creation, and unlocks the mutex when the lock is destroyed (for example, at the end of a function scope).

Modifying the above code again results in:

void operator()()

{

for(int i = 0; i < 100000; i++)

{

lock_guard<mutex> lock(this->m);

// The lock has been created now, and immediatly locks the mutex

this->counter++;

// This is the end of the for-loop scope, and the lock will be

// destroyed, and in the destructor of the lock, it will

// unlock the mutex

}

}

This code is also exception-safe because when an exception occurs, the lock's destructor will still be called, resulting in an unlocked mutex.

Remember, you can create your temporary scopes in the following way:

void long_function()

{

// some long code

// Just a pair of curly braces

{

// Temp scope, create lock

lock_guard<mutex> lock(this->m);

// do some stuff

// Close the scope, so the guard will unlock the mutex

}

}

Closing

I promised in the previous article to explain why the printing of “Hello World” and “Parallel World” sometimes went wrong. I hope you understand now that sharing resources between threads without synchronization can cause problems.

I will be a bit lazy and redirect you guys to this stackoverflow question. To fix the output of cout, create another mutex, and each thread should lock that mutex before sending something to cout and, of course, unlock it when it’s done.

I hope you enjoyed the article. Next time, we’ll cover condition variables, another widely used technique to synchronize threads.